A few weeks ago (in October 2021) I did the toughest ride I have ever done. The challenge was to ride 1,850 km and climb a hundred cols totalling 38,000m of elevation in ten days. By any standard, this is a pretty serious endeavour. Just looking at the numbers sent shivers down my spine: it was obvious that the sheer relentless nature of it would push me to my limits.

If you have read my accounts of the adventure (Cent Cols Challenge Corsica) you will know that I ultimately succeeded. Towards the end, however, there were times when I seriously wondered if I would make it.

In the following paragraphs I wear my cycling coach’s hat to answer the question: what does it take to ride a Cent Cols Challenge?

Advice for future first-time CCC riders

Why did I do this?

Firstly, why did I sign up for it? It’s worth asking the question, because completing a CCC requires many things, but above all a real determination to do so.

I had multiple motivations for the event, but the main one was the sheer challenge of it. It was clearly well beyond anything I’d done before, and I wanted to see if I could do it. Would I crack, and if so would it be mentally or physically? Was it reasonable for a 62 year old to take on such an extreme physical challenge? Would I even enjoy it? And as a cycling coach, what would I learn from the experience that I can pass on to others?

I loved the idea that the event was in Corsica: a little-known cycling paradise that I was keen to get to know much better. The fact that the event was a group ride supported by a reputable professional organisation was an additional positive factor.

Technical analysis

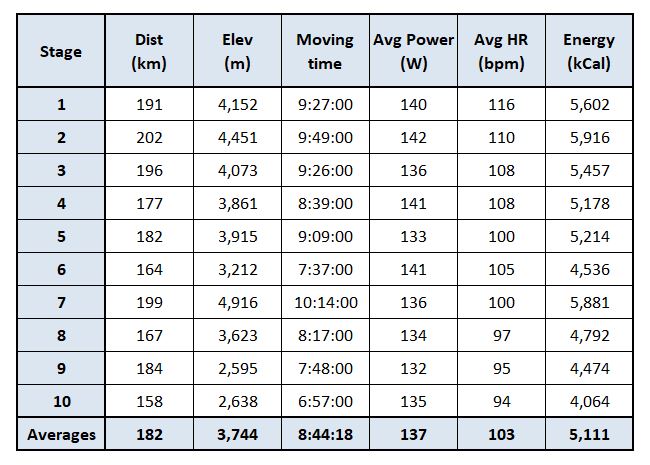

The table below gives the stage-by-stage breakdown for the key ride data. The main take-aways are:

- The days are long. We started half the stages at 07:30, the other half at 08:00. I finished 7 of the rides between 18:00 and 18h30, and only one of them before 17:00.

- My average moving time per stage was 8h44, with around 1h15 stopped at feed stations or to take photographs. The longest day was 10h14 (moving time, 11h08 in total) and the shortest was 6h57.

- My average calories expended per stage were 5,111 kCal, with a high of 5,916 kCal and a low of 4,064 kCal.

- My average power per stage (moving time only, but including zeros) was 137W. The highest average power was 142W and the lowest was 132W.

- My average power was highest in the first 2 stages at 141W, and lowest in the last 2 stages at 133W. The most likely explanation is that I was fresher at the start and at the end I was both fatigued and suffering from pain in my Achilles tendon.

- My power distribution was remarkably constant across all 10 stages, at 39% in Z1, 44% in Z2, 14% in Z3 and 2% in Z4. (There was one exception to this constant power distribution: Stage 9, where I spent more time on Z1 and less time in Z2. This could be explained by Stage 9 having the least total climbing, but much of it being steep, pushing me into Z3).

- My heart-rate (HR) distribution was very different to my power distribution, and changed significantly from the first to the last stage, pointing to my increasing fatigue. It dropped from 116bpm to 100bpm from Stages 1 to 5, recovered to 105bpm for Stage 6 and then dropped to 94bpm by Stage 10.

- It is instructive to compare the power and HR distributions on Stage 9. Here I spent the highest proportion of moving time in Z4 of all ten stages, according to the power distribution, but none at all according to the HR distribution. This is almost certainly due to fatigue.

- I measured my resting HR (RHR) and Heart Rate Variability (HRV) every morning, as soon as I woke up. My RHR went from daily values of around 40-41bpm in the previous week to 44bpm on the morning of Stage 1, reaching a high of 53bpm on Stage 5, and then stabilising around 46bpm (+/- 1.5bpm) for the last five stages.

- My HRV values, as you would expect, did the opposite. I began Stage 1 with HRV in the normal range, but from Stage 2 onwards it dropped below normal, improved a little for the last 5 stages but remained below normal until the end of the event. Both increased RHR and depressed HRV are signs of increased stress.

How I rode it

The above data is rather dry, reducing what happened down to impersonal numbers. These are useful, but they are only part of the story. Equally important is how I rode on a daily basis, and especially my decisions with respect to clothing, pacing, nutrition and post-stage recovery. Taking the right decisions in these four areas is crucial to a successful ride.

Clothing

This may come as a surprise, but according to the organiser, more people have failed to finish CCC events due to poor clothing choices than for any other reason. Conditions change very quickly in the mountains and it is not unusual to start with warm and sunny weather in the valley, only to be met by temperatures 15°C to 20°C lower, strong winds and rain or even sleet on the summit. Add the wind-chill factor of the descent and the apparent temperature can be well below zero: you are then in serious trouble if you don’t have adequate clothing with you.

I was caught out on Stage 2. We stopped for lunch after the first 7 hours, at a warm, sunny spot. The temperature was 22°C. We had another 60 km to ride and a final climb similar to the one we had just done, in a north-east facing valley, warm in the morning sun. I gave no thought to the likely conditions 3 hours later and 1,200m higher up, in a valley that would now be in deep shadow. I had access to all my kit, but I was sure that arm-warmers and a light summer gilet would be enough. In fact, the temperature was only 5°C at the top, and there was an icy wind. I am not at all sure I could have completed the 14 km descent without the loan of an emergency jacket from the support car.

Haut-Asco (1,400m). Dressed to descend at 14°C in the sun.

Haut-Asco (1,400m). Dressed to descend at 14°C in the sun.

I made another silly mistake on Stage 5, where it was threatening rain as we took our lunch. The weather radar app on my phone told me the rain storms were all moving away from us and we would be clear. Having learned a lesson on Stage 2, I nevertheless took my rain jacket, but I didn’t bother with my neoprene long-fingered gloves. Unfortunately, it not only rained, very heavily, it also hailed, equally heavily. At least my trunk and legs were warm enough, so I had no risk of hypothermia, but the final descent with frozen hands would have been very long, very unpleasant and potentially dangerous had I not been saved by timely access to my gloves in the support car.

Key lesson: it’s not enough to bring the right clothes with you: you must have them on your person when you need them!

Pacing

Pacing is the next most important area to get right. Everybody knows that you should immediately settle into a pace that you can sustain climb after climb, day after day, but it is very tempting to push a bit harder on the first day. You feel fresh, the adrenaline is pumping and you don’t want to be left behind or appear to be the weakest in the group. In spite of deliberately holding back and being amongst the last to finish each climb on the first day, my HR response on Stage 1 was still closer to what I would expect in a sportive, with 49% in Z3 and 10% in Z4!

What does it mean in practice, to ride at a pace that you can sustain climb after climb, day after day? The answer varies from person to person, but if you do enough training for the event, you will know by experience what power and/or HR range to target and what margin for error you have. In my case, I knew that whereas in the context of a one-day race I could make the climbs in Zone 3, perhaps with a few efforts in Z4, in the CCC I would have to ride a lot slower. I thus used my power meter to ride all the climbs at Z2, with just an occasional effort in Z3 when I felt I could do so without any risk.

Nutrition

Nutrition is only slightly less important than pacing. If you don’t “feed the machine” adequately, you cannot hope to finish. As noted above, my average expenditure of calories per day was over 5,000 kCal, which meant I had to consume an equivalent amount (plus the base load of ~2,500 kCal). This is a lot of food. Hoping to consume enough at “official” meals only, i.e. breakfast, the two feed stops and dinner, is illusory, resulting in 3-4 hour gaps between meals and sooner or later running on empty. I thus filled my pockets with figs, bars, and honey waffles and ate three items per hour between the stops, which worked fine.

In terms of hydration, I drank around 300ml of water per hour. This is on the low side and it certainly wouldn’t have done any harm to drink more. I drank mostly plain water with every second or third bottle containing an electrolyte mix, but no carbohydrates. This is a personal choice and there’s no doubt drinking an energy mix is an effective strategy for many people.

A final thought on nutrition: this is absolutely not the moment to think of losing weight (or to have any concern about putting on weight). In spite of eating copious amounts of energy-dense carbs for ten days, my weight barely changed. If anything it increased slightly, a sign that my nutrition was effective.

Recovery

The last key area to get right is recovery. This was my top priority as soon as each ride ended. By far and away the biggest contribution to recovery is made by high-quality sleep, so I did as much as I could to favour this. The rides always finished too late to enjoy a siesta before the briefing and dinner, so I made sure that I could get to sleep as quickly as possible after dinner. This involved a disciplined process with the following steps:

- Check my bike, put it away safely.

- Eat some cake and drink a carton of chocolate milk (the carb/protein mix is ideal to start the process of glycogen replacement and muscle repair)

- Find my bag, check in to the hotel, go to my room

- Strip off and enjoy a lengthy hot shower, washing my kit at the same time

- Wring the wet kit out and hang it up to dry

- Put on warm clothes and compression socks, do a few gentle stretches and yoga movements

- Drink water

- Lie down on the bed, reply to important messages and emails, write up my notes from the day

- Go down for the briefing and dinner. Drink plenty of water during dinner, avoid or limit alcohol.

- Back to the room and sleep as soon as possible. Try to avoid screen time after dinner!

How I trained for it

I signed up for the CCC Corsica less than five months before the event was due to take place, so in terms of specific preparation I didn’t have much time. I got away with it, however, because I regularly ride in excess of 10,000 km per year and I was building on two years’ worth of training for the Tour du Mont Blanc. At 340 km and 8,400m+, the TMB has a strong claim to be the toughest of the one-day events in the mountains.

Both the TMB and the CCC are at the extreme end of what is possible without cycling through the night. The TMB is a one-day event and as such is tougher than any one day on the CCC, but the CCC is relentless, continuing for ten days (with a rest day in the middle). The intensity must therefore remain low: there is no question of doing the climbs at threshold (as one might do on the Etape du Tour, for example).

My training – initially in preparation for the TMB and from early June for the CCC – was thus predominantly low-intensity endurance-based, otherwise known as long slow distance (LSD). To put some numbers on this: in the first 9 months of 2021, I trained, on average, for 18 hours per week. I cycled 176 times, covering 12,500 km and climbing over 225,000m. 47 of these rides were 5h or longer; 18 were 7h or longer, and 3 were over 9h. The intensity breakdown was 81% in Z1 or Z2, 17% in Z3 and just 2% in Z4. (N.B. I had intended the intensity distribution to be closer to 90% Z1/Z2, but I discovered during a lab test in June that my Z2 boundary was set too high, so my early training was often a little too hard).

I usually went without food for the first two hours, then later for the first three hours of a ride, in order to stimulate increased fat-burning. I believe this worked but have no way to prove it. All I can say is that I didn’t feel any hungrier than normal during training, and I never ran out of energy, either in training or during the CCC.

I complemented my on-the bike training with two hours of cycling-specific strength & conditioning classes per week, and one cycling-specific Yoga class. These were run on-line over Zoom and could thus be followed from anywhere. I credit them with giving me the leg strength to push on, day after day, and the core strength and flexibility to finish without suffering any injuries or pain in my back, my shoulders or my neck.

I took a two week break from training before the CCC, to ensure that I was as fresh as possible. Given the amount I had ridden in the previous 9 months, I don’t think I lost any fitness at all in this time, but I certainly gained freshness and was raring to go.

What I learned

My training was effective. I achieved the goal and finished the challenge. At no time did I feel that my cardio-vascular system or legs might not be up to it. I am sure that the three hours spent per week on off-the-bike training were far more valuable than an extra three hours of cycling would have been.

I didn’t pay enough attention to my body. Although heart and legs were OK, I was developing more and more niggles. In most parts of my body they came and went, but from Stage 6 on I had persistent trouble from one of my Achilles tendons, which has never happened before. This was almost certainly caused by the abnormal load, combined with an increasingly tight and shortened calf muscle and possibly exacerbated by fatigue degrading my pedal stroke. I should have spent much more time in particular working on releasing tension in my calves after each ride.

Motivation is essential. I knew why I was doing it, and I had answers for the doubts that crept in with increasing fatigue or bad weather. Be aware, however, that it’s one thing to ride a CCC in generally good weather, as I did. It would be quite another to ride it in continuous rain.

Stay lucid. As noted above, I learned that when fatigue builds I may lose lucidity and stop thinking clearly. This becomes a trap that can only be sprung by external intervention or a shock. Being aware of the trap may help reduce the risk.

Advice for future first-time CCC riders

I can only make a few general remarks because the advice and training programme you need is highly individual, and depends on your starting point. There are no hard-and-fast rules and exceptions certainly exist.

By far the biggest demands of this event are physiological and psychological. Yes, you will have an easier ride if you have a high power to weight ratio, if you recover fast, and if you have strong technical skills, but all these pale into insignificance compared to the need for excellent aerobic endurance and the mental fortitude to go the distance.

These are my Coach’s Recommendations for the best chance of a successful and enjoyable ride:

- Only experienced cyclists should apply. Build up to riding a CCC over several years by gradually increasing your training load. A good target is 10,000 km per year.

- Use a bike designed for endurance, not for racing. Make sure it has the lowest possible gears. A ratio of 1:1 (e.g. 34-34) is the minimum you should accept. In this regard, Campagnolo and SRAM offer better options than Shimano (respectively, 32-34 for the Chorus, 33-36 for SRAM’s Red or Force eTap AXS and even 30-36 for the Rival eTap AXS).

- Get an endurance-oriented bike fit.

- Aim to do 90% of your training at endurance pace or below. This may feel ridiculously slow at first, but you should get used to targeting hours on the bike rather than distance ridden. Endurance pace means no higher than Zone 2 (on a 5 or 7 zone system).

- Build your time on the bike progressively. You should work up to doing several 8-9h rides as well as several back-to-back 6-7h rides.

- Enrol in a cycling-specific strength & conditioning class, and a cycling-specific Yoga or Pilates class. These will help you build both leg and core strength, and teach you how to release tight muscles, thus reducing the risk of injury.

- Learn how to ride in the mountains, making long climbs and long descents.

- Get used to riding in the rain, especially when it is cold. Test different equipment options and find out what works best. This is not an area to save money.

- Gain experience by riding at least one 5 or 7-day event, such as the Route des Grandes Alpes, or, if you enjoy the competitive element, the Haute Route, the Tour Transalp or the Giro Dolomiti. A typical day at these events is less than 75% of a typical day at a CCC, so they are good platforms to build experience.

- Complete your training at least one month before your CCC event. The final month should be targeted at maintaining your fitness while eliminating your fatigue.

Do not read the above recommendations as binary. It is possible to succeed without following all of them, but you would most probably find it harder and above all less enjoyable. And what is the point if you don’t enjoy it?

Support from Alpine Cols

As a team of professional cycling coaches, we are always delighted to talk about your objectives and training needs. We work with people at all levels, from newcomers to national champions. Contact us for a chat, and consider joining one of our coaching camps to improve your skills and technique, or one of our cycling tours to enjoy the best of the mountains.